I am not a writer, but I am good at analyzing things from an economic, technical, and product perspective to spot opportunities and value. Having been in crypto for years, I had assumed that by now, in the year of our lord twenty-twenty-three, it would be clear what the use case for “crypto” / blockchains / web3 / DeFi, or whatever you want to call it is to the mainstream at large.

It hasn’t happened, despite the space growing by leaps and bounds, largely because our spokespeople apparently couldn’t explain themselves if their lives depended on it, as the following video painfully showcases their GPT-3 Markov chain-like rambling:

Such videos contain an untrue assertion, that crypto has no fundamental value except being some kind of casino (which it also is). Valid criticism should be welcomed but said implication often made by crypto critics is a pure, unadulterated lie and more of a moral judgement on a subset of it.

That’s why I wanted to lay out why I think it’s a fundamental innovation that realizes new economic efficiency and value, along three points:

“Crypto” fundamentally reduces the economic transaction costs of trust for a common set of economic transactions.

In economics, lowering economic transaction costs allows more mutually beneficial transactions to take place and increases the efficiency of a given market where those costs were reduced.

This, in turn, allows more people to securitize and trade value to apply market solutions to problems.

I will explain one and two, and provide examples of three.

Economic transaction costs and market failures

Our first assertion mentions economic transaction costs, which need to be defined in context. It also calls out common transactions, which can be understood to be holding value, moving value across space and people, or creating securities and debt. The technology is certainly not limited to this and we will expand “transactions” to almost any bilateral action taken on blockchains. But, let’s start with the first.

What are transaction costs?

The economics definition is not simply say, the transaction fee you pay for different bank wires or a Paypal payment. In economics, transaction costs refer to any costs associated with making an economic transaction that isn’t the cost of the transaction itself, such as the costs of finding and communicating with potential trading partners, negotiating and drafting contracts, and enforcing agreements. This is a very wide definition and gets at the fact that these costs are practically in everything, and if they aren’t a small part of the total costs of business, they are a big drag factor to creating value and are considered a market failure mode.

For example, what are the transaction costs of shopping around for emergent cardiac care (e.g. having a heart attack)? It’s the cost of dying while looking for a better price, and thus you are likely to resign yourself to be a price taker for the closest cardiac surgeon around who can take a look. This is why medical care is so regulated because industries like healthcare with high transaction costs, high information asymmetry and inherently perverse incentives to overcharge desperate people are not usually efficient markets and do not follow the efficient market hypothesis as well as the market for say wheat or apples.

To make the world work, trust and open information are used to lower these costs by reducing the need for expensive mechanisms, such as legal contracts and actions, to ensure that trading partners or customers fulfill obligations and abide by terms and conditions.

However, building trust is not free, it also comes with its own costs such as time, effort, and potential loss in the repeated transactions that are required between entities to build rapport and expectations. It could also be more difficult to achieve, e.g. between strangers or across cultural or national boundaries. You can model the economic transaction costs of trust as:

(G-S) * p > (1-p) * L

G is the potential gain if the other actor behaves honestly.

S is the cost of monitoring the other actor and enforcing sanctions if they behave dishonestly.

p is the probability that the other actor behaves honestly

L is the potential loss if the other actor behaves dishonestly.

This expresses the basic economic model of the expected benefit and risk of a single transaction with someone else, which is used to determine if the actor goes through with it or even bothers to consider it. It asserts that an agent will enter into a transaction if the inequality evaluates to true, where potential gain (G) minus the costs of monitoring and enforcing sanctions (S) against the other actor, multiplied by the probability that the other actor will behave honestly (p), is greater than the potential loss (L) multiplied by the probability that the other actor will behave dishonestly (1-p).

This means there is a world of mutually beneficial transactions between people that could happen but don’t because either S is too high (they live in a country with different contract laws) or p is too low (I can’t trust this manufacturer to not steal my idea). Raising p over time is expensive, and is why businesses develop brands and why financial institutions aim to develop a moat of reputation.

Effects of reducing transaction costs

In economics, reducing transaction costs in a market is one of the best things you can do, it is one of the most common market failures, and gives rise to the next most common; externalities. Externalities are called as such because they are free-rider problems outside of the context of the market, and are not able to be priced by said market either, often preventing a market from solving to Pareto-efficiency in terms of distribution of scarce goods and services for the maximal subjective benefit of everyone.

For example, it is profitable to pollute the planet because little Timmy’s mom finds the transaction costs of invoicing Exxon Mobil and all car drivers for his asthma care costs too high, thus Exxon Mobil and their customers are free riders in that they don’t pay all costs associated with the use of their product. This sort of thing often throws a wrench into the finely tuned theoretical machine of “efficient markets” that are often touted by laissez-faire economic liberals.

Eliminating these transaction costs obviously causes more transactions to be made, and for subjective value to be maximized from everyone’s perspective. In the above example, if every kid like Timmy could bill every driver and oil company fairly (for contributing to his asthma or climate change), gas would become expensive, people would use something else and climate change/pollution could actually be solved by “consumer choice” like everyone imagined in the 90s. Hopefully this illustrates how central and fundamentally and economically beneficial it is to reduce these transaction costs in most markets.

Basics of valuing blockchain networks

Now that we understand what transaction costs are and how they affect markets, we need to get a common understanding of the fundamental functional drivers of value for a blockchain network and why bitcoin is still the most valuable network by capitalization, or alternatively why no one gives a shit if there is a “faster” Ethereum around. A great place to start is by explaining why double entry ledgers and bookkeeping were an innovation when it was invented in 1400s Italy by merchants and then brought into dominance by the Medici Bank.

The linked article is good, but to save time and frame it in the context of economic transaction costs, double-entry ledgers reduced the transaction costs of trust between borrowers and lenders, because it prevented the bank from unilaterally lying and saying you owed more than you did. This allowed larger economic actors like the Medici Bank to exist and thrive. In fact, most of the modern practices of accounting and the economic benefits they entail, such as enabling large complex operations like a global corporation to be audited by investors and the public, are owed to double-entry bookkeeping.

Just as double-entry ledgers were an innovation, it helps to think of blockchains as an innovation that uses cryptography and redundancy to create a many-entry ledger and a native asset on top of it.

This ledger is maintained in an open, digital manner via an economic game that incentivizes monkeys to perpetuate the chain honestly according to a set of rules defined by the game. A Schelling point, or social norm, is formed at a critical mass of history and nodes/monkeys involved. At this point, other user monkeys can reasonably treat using the ledger as decentralized and without direct counterparty because of the cryptographic guarantees and the cost of coordination across so many monkeys to try and compromise those guarantees.

Qualitative valuation models

In this framework, the general value of that ledger and its asset is approximated by the following three components:

Metcalfe’s law: The usefulness of a network is roughly the square of the number of people using it, which can be approximated with the number of nodes in the network. This is assumed because more interesting things can happen when more people are part of a network, and can be considered the “general usefulness coefficient” of the network.

General usefulness = # of nodes ^ 2

Value of network ~= # of nodes ^ 2

Value-weighted Lindy effect: Mathematical idea that the time a blockchain ledger spends alive and uncompromised is roughly half of the lifespan you can blindly expect it to live. Capital will want an old ledger as it is expected to have a longer life. Value weighting means that before most capital trusts any ledger enough to live on top of it, it wants to reduce the risk it takes by watching what happens to capital that’s already on the ledger. If adversaries or malicious actors somehow compromise the ledger or its economic game and steal the money, or come close to it, capital will stay away. If nothing bad happens, more capital is attracted.

Perceived risk by capital ~= ∫ Lindy (time still alive) * Value on-chain

(integral over time of value on-chain)Max capital limit of chain ~= ∫ Lindy (time still alive) * Value on-chain

Expressivity: Much like Metcalfe’s law, but the idea that interesting transactions happen not only as you scale nodes, but also as you add more types of transactions or more expressivity (e.g. Turing completeness). This doesn’t really have some analogous expression like the other two and is much more qualitative and relative.

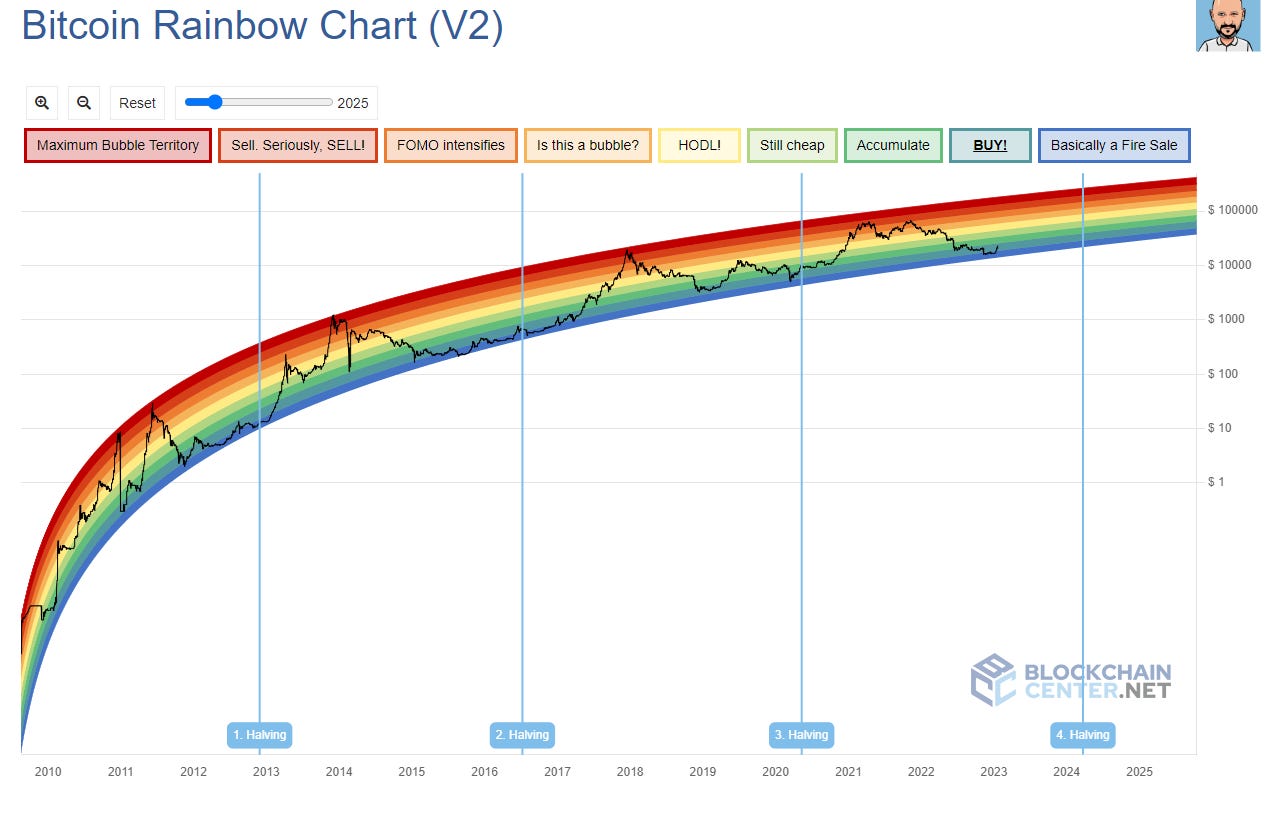

Over time, these three factors tend to go up as long as the blockchain goes uncompromised, and they are why the observed value of these chains over time fits logarithmic projections well, like the infamous rainbow chart (to be clear, these log projections are not necessarily good prediction tools, we are simply theorizing why the past looks the way it does).

Trad-fi valuation model

As a quick aside, I can already hear boomers wheezing about how the above metrics are for pansies who didn’t have metal playgrounds as kids and whatnot. But, it is actually helpful to try and value blockchains as traditional finance does brick-and-mortar businesses, and you can, though almost all current networks are money-losing businesses. This is possible by considering blockchains as businesses that sell space on the ledger. This revenue goes towards the economic game that perpetuates the ledger, in what Satoshi hoped would be a virtuous cycle of growth. The value of this block space can range from cheap plastic crap to Veblen good, but can be approximated by the qualitative metrics above as well as say the dollar amount folks are willing to pay for said space.

The production cost for block space is pretty much the cost of making an economic game to perpetuate the chain and decide certain things like who gets to make the next block, and which transactions are included. This is usually mining, or staking, which is just mining with the compute cost abstracted out to be just capital, thus being cheaper and energy efficient.

The revenue from block space is simply the transaction fees collected selling the produced secure block space and its guarantees to users. Thus to value blockchains on a discounted cash flow basis, you take:

Value = P/E Ratio * ( yearly fee revenue - yearly mining/validator disbursements )

In this model, Bitcoin loses money because it doesn’t charge enough fees on the $15 trillion in economic value it settled in 2022, and Ethereum is really the only current asset that has ever had positive cash flows. All other chains are pretty much turbo money-losers. This makes sense if you think of them as products in their growth phase that subsidize users in exchange for growth. We will get to what this product really is.

Blind men and the elephant

Frustratingly, a combination of obfuscation and poor industry messaging has allowed outsiders to control the narrative about crypto as technology, and so far that narrative is a derisive one that asserts it has no “real” use cases past “speculation” and mere gambling.

This is a red herring however, a false dichotomy borne from the fact that the real value of crypto is non-obvious to domain experts in the fields relevant to “crypto”, such as economics, computer science, finance, and cryptography. Knowledge from each field is required to understand the whole picture. This leads to said experts feeling each part of the elephant, fitting what they grope into the normative framework of their own domain while concluding that crypto is fucking bullshit because the incomplete picture they have doesn’t look novel or valuable. Concisely, here is the relevant understanding contributed by the knowledge of each domain:

Cryptography: Understanding the powers granted by public-private key pairs held by many users, and the security guarantees or assumptions in such schemes.

Finance/Economics: Knowing how and why incentives are structured the way they are in the crypto-economic game created by blockchains to perpetuate themselves, as well as how humans value things.

Computer science: Knowing the constraints and trade-offs made from the perspective of a distributed network that shares state with redundant data structures.

Conversely, the below misunderstandings about crypto are prone to occur from experts in each domain:

Cryptography: “There is nothing new about the cryptography used in cryptocurrency, because the economic game created is not appreciated by me, the expert cryptographer.”

Finance/Economics: “Crypto assets have no ‘backing’, and thus are elaborate pump and dump/Ponzi schemes because the value of novel cryptographic trust assumptions in blockchain economies to users are not appreciated by me, the expert economist.”

Computer science: “Blockchains are inefficient, redundant data structures whose use cases are better served by a SQL database because the economic value of the state maintained on a battle-tested ledger (and its redundancy) is not appreciated by me, the expert computer scientist.”

Fiat liquidity and the first crypto use case

It’s easy to be obtuse about these arguments from theoretical frameworks and pop-econ, so what are the concrete manifestations of this claimed value? Let’s start with one common refrain, that Bitcoin has “no productive use” or utility, or that the economic activity that happens on crypto rails is “self-contained” and isolated from the “productive” part of the economy.

This is verifiably incorrect because it ignores the widespread fiat liquidity enjoyed by the native assets of the most established blockchains (BTC or ETH). Earlier we established how these networks grow more valuable as more monkeys around the world participate in them, and in turn, as more monkeys value the network and its native asset, said asset gains more and more of this liquidity with “fiat” in general.

Bitcoin miners cash out $20 million around the globe every day, so we know this liquidity exists. This liquidity is central to the first “Wright Brothers” moment and use case for the first blockchain, Bitcoin.

To illustrate what I mean, the diagram below answers why “volatility” or unit of account issues do not hinder the transfer of value use cases of bitcoin because transit and settlement time is low. It doesn’t matter how stable bitcoin is if I’m only spending 15 minutes holding it to route a transfer of value to another person who will cash it out immediately.

Similarly, fiat liquidity enables the “cross borders with portable value” use case as well:

With Ethereum and its expressivity in having smart contracts enabled by a Turing-complete scripting language and VM, there are richer and more complex financial use cases that make up an economy, such as making a new security token, collateralized debt, stablecoins (tokens pegged to the value of a fiat currency like the dollar), automated markets for different tokens, etc.

This economy is not isolated and connects to the real world through fiat liquidity where value is cashed out locally by participants around the globe. This is how transaction costs are reduced! You do not need everyone to adopt Bitcoin, Ethereum, or any other crypto asset like they are forced to adopt their local government-issued fun bucks, as long as there is fairly deep and widely available liquidity with fiat, which is recently been more true with $15 trillion of value settled on the Bitcoin network in 2022, and $9 trillion of value settled by Ethereum in the same year.

Remittance and minting of stable-coins

Since late 2018 on-wards, stablecoins, or synthetic dollars/yuan/yen etc. as tokens on-chain, have seen growing adoption. Given the top countries by crypto adoption, what reason might you suppose for the list looking like it does below?

Most of these countries on the list of top crypto-adopting nations (Vietnam, China, Pakistan, Nigeria, Russia, China, Brazil) do not have good local financial systems or widespread access to secure and trusted financial institutions. Dollar hegemony has also produced a Schelling point, like we established these networks do, between people living in these countries to use the dollar as a store of value.

However, the dollar as a reserve currency incentivizes their governments to confiscate local dollars for foreign trade and their own debt servicing purposes. Thus holding becomes a problem, and this creates a need for people in these countries to hold dollars safely without using something that looks like a bank.

Ethereum, and other smart contract platforms, enable the use of its market capitalization and fiat liquidity to unilaterally mint synthetic dollars, or any other currency (stable coins). This is done via collateralized debt and automated smart contracts to lend and liquidate lenders who borrow fiat stablecoins against ETH. Since ETH has a lot of liquidity around the globe for dollars and other fiat, you can issue fiat denominated debt by holding ETH as collateral from your borrowers. Said tokens can then be circulated to help people trade in and hold value in “dollars”. An example of this is Liquity, its LUSD stablecoin being completely backed by ETH at all times. The downside to this approach is that it can never scale past the liquidity available for the blockchain’s native asset.

Of course, more centralized approaches are possible where a company like Circle or another regulated entity like the National Australia Bank, can issue stablecoins that are backed by real dollars held somewhere. This allows scaling so that more dollars can be held on Ethereum than the market cap of Ethereum.

This capability is why that list looks the way it does, as blockchains reduced the transaction costs of obtaining and holding dollars in places where the local bank outright steals them from you.

Scaling and Layer 2s

The previous section, put in front of the typical crypto critic, would likely garner another common trope of crypto criticism; that blockchains like Ethereum are inherently un-scalable and too inefficient because of their redundancy and will fail to serve “global” or real use cases, like sending dollars across borders.

This was true for a while and still is true for say Bitcoin, since it can only do ~7 transactions a second, with Ethereum not having much better to show than ~20-25 TPS. Higher throughput in blockchains runs up against one of the constraints, communicating that much information to every node within a short time frame, so consensus can be reached. That much info piling up also means every node needs space to store and retrieve a large history.

However, crypto is a rapidly advancing space, and we discovered the scalability benefits offered by validity roll ups, or having cheap computation that happens off-chain and is verified and committed to by a smart contract that is on-chain. Thus you can essentially compress the information that needs to be shared for high throughput uses with a cryptographic proof, and still enjoy the benefits of widescale decentralization and the security it entails. This description simplifies some technical details, but conveys the concept generally at a high level, see Vitalik’s great summary of the concept.

Layer 2s and the discovery of validity roll-ups enable $0.01 to $0.10 transactions of these stablecoins we mentioned before. This reduces the economic transaction costs of trust and security by enabling people in Vietnam and Pakistan to hold and store value in foreign currency without a bank, and without paying high fees to use scarce block space on secure ledgers like Ethereum.

This also allows remittances from the United States and other developed countries by immigrants to their families at home for a fraction of the cost of an international wire transfer or Western Union, because it no longer goes through a complicated web of trusted intermediaries employing millions of people and requiring thousands of local and international legal apparatuses to mitigate its inherent perverse incentives.

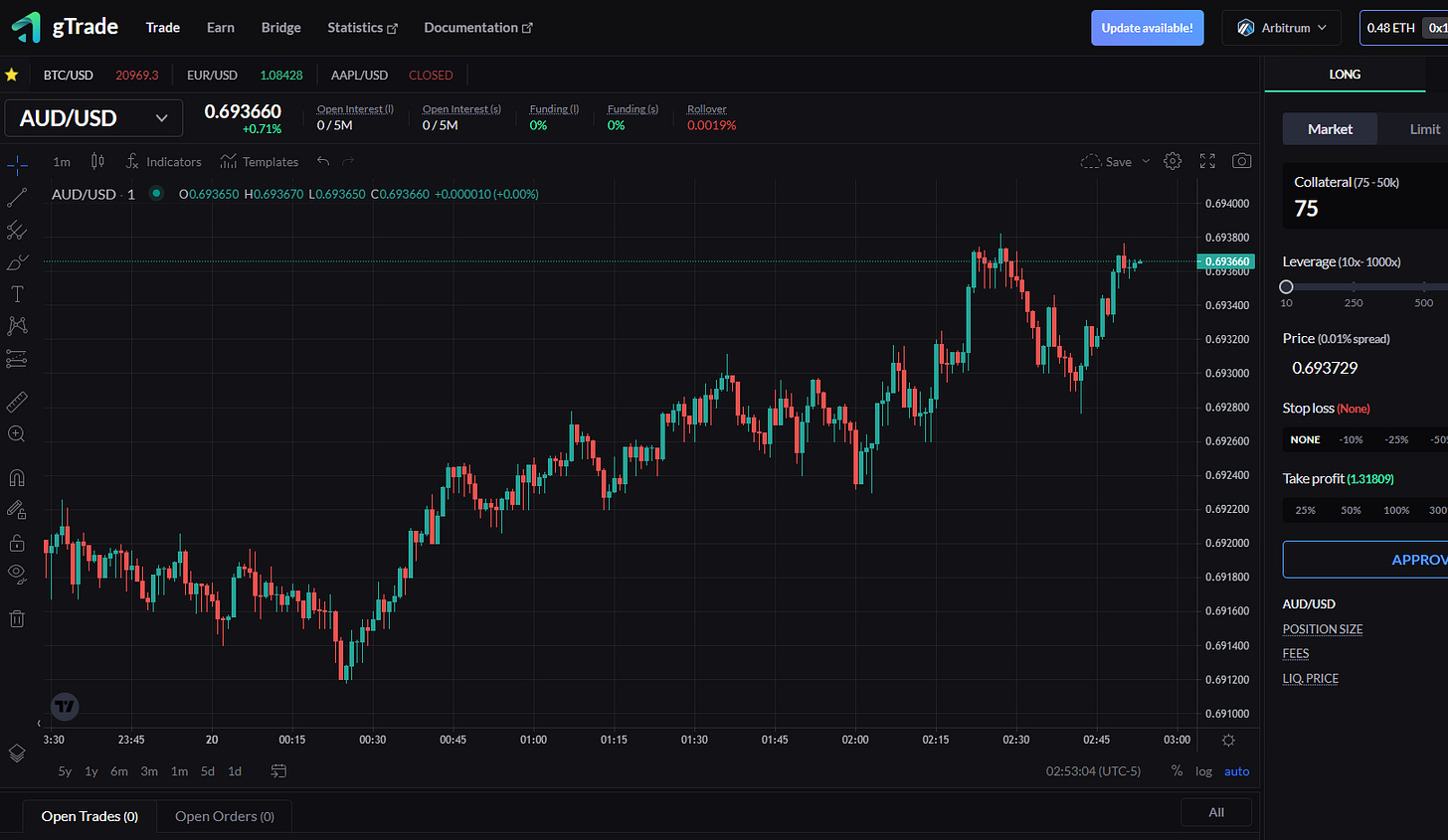

Knowing this capability to mint fiat tokens on-chain for circulation and trade, and having a viable solution to scaling, it is not hard to see that very useful, neutral, and trustless decentralized foreign exchanges (such as gTrade) between these stablecoin tokens are likely to emerge, reducing the transaction costs of people around the world for opting in to hold their wealth in the fiat currency they want, instead of the one they are born into.

NFTs and easy, cheap securitization

Another new superpower granted to users by fully expressive and decentralized blockchains is Non-Fungible Tokens, which reduce the economic transaction costs of issuing your very own security to the world and have it available to global liquidity. Our treatise so far on lowered transaction costs driving much of the fundamental economic value for crypto is relevant here as well.

What are NFTs?

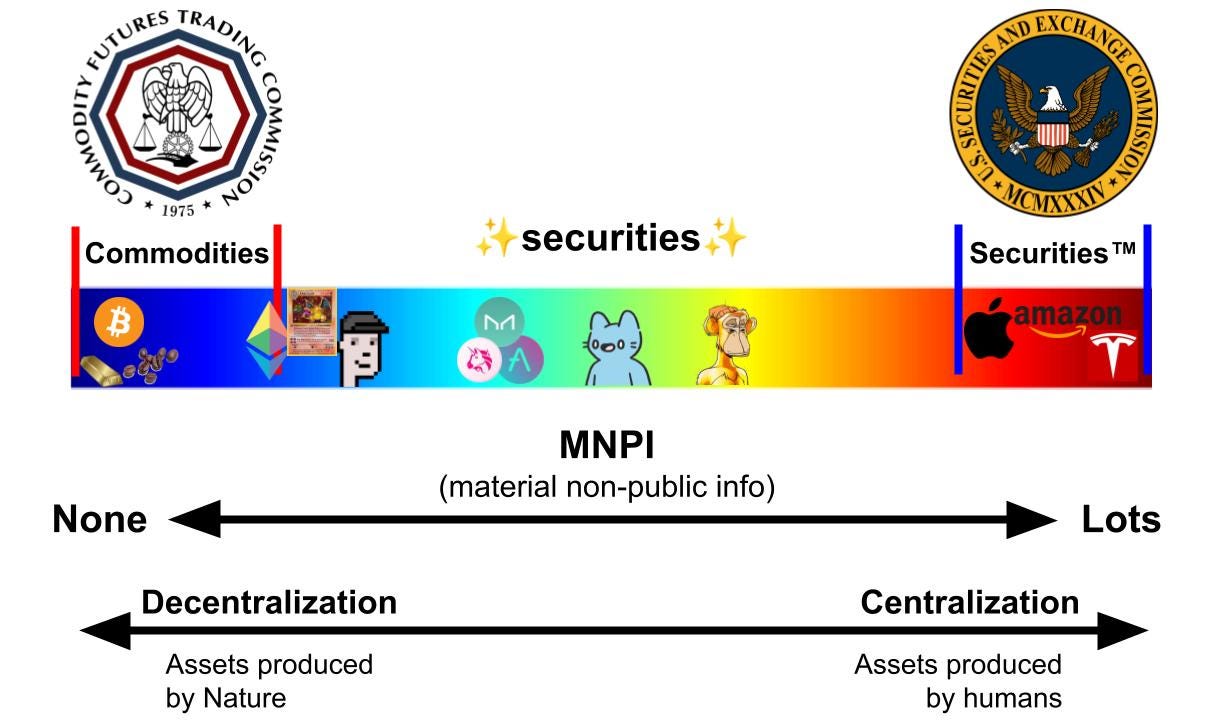

After people made fungible tokens like stablecoins, they realized they could make tokens that were unique too, and not fungible with other tokens from the same contract. These are essentially objects on-chain, with a facsimile of property rights around them governing who is allowed to move them, change them or mutate them, destroy them, hold them or sell them. However, the best way to describe them at a higher level is as securities, as lawyer and law professor at the University of Kentucky, Brian Frye explains very well in a Bankless episode.

Of particular interest is the “securities spectrum” presented in the episode, which shows NFTs as “sparkling securities”, for things with lower amounts of material non-public information than currently understood securities (e.g. shares of a company).

NFTs can be better understood by considering the information they contain and secure as well which includes;

Who deployed the contract (made the security), or created an instance of its security (mint an NFT).

Who holds the object currently.

The provenance of the object (its full history of changing hands or being mutated and changed according to rules in the contract).

Thus, NFT art and “right click and save” arguments against it simply misunderstand what part of the NFT is important (it’s not the jpeg, but the signature of the artist), just like how some do not understand that the signatures on real paintings are the most valuable part of the object. Art NFTs then can simply be about buying the ability to be on the public list of owners and patrons of an artist. This is essentially a financial security that is a bet on the career of that artist.

In our framework of transaction costs; NFTs reduced the economic transaction costs for artists to earn a living by eliminating their need to compete to be selected in galleries, chasing commissions, and working with auction houses to attain clout and sell their work.

Other NFT use cases

Other NFTs can function as tickets (and old stubs), passes, club memberships, degrees, collector’s items etc. The real application of NFTs then is as securities that are cheap and easy to issue, coming with compatibility for financial rails that connect them to global liquidity. This ends up enabling more securities to be created, to be applied to solving problems where market solutions were infeasible before.

As we covered before, Trad-fi securities require lot of regulation to fix perverse incentives inherent to high information asymmetry (lot of private privileged information, enabling insider trading advantages), needing direct counterparties and need to trust custodians. This increases transaction costs of making new securities so that only fairly large corporations or financial institutions can issue them. Making new securities is simply applying market solutions to a particular problem (need for capital, amortizing risk or cost, price discovery of commodities).

Ethereum/smart contracts reduces transaction cost of creating new securities via ERC20 tokens and NFTs, since it comes out of the box with rails to trade it, there are Automated Market Maker protocols in the Ethereum ecosystem to provide liquidity and anything else you want to program for your new security. This allows for novel use cases, and micro applications of markets to distribute scarce resources. But let’s take a look at my favorite concrete example so far:

Eric is a smart guy, with valuable knowledge and expertise that people always want to question him on to apply to their problems. He made his own security as an NFT, the “Orb”. It allows its holder to use the NFT to deliver a question to Eric, which he promises to answer (lest his orb lose value). Said Orb has a built in auction mechanism and Harberger tax to create a market for Eric’s time and expertise as a good distributed systems software engineer.

Eric basically:

Created a personal scale market for a new security, which is nearly impossible with traditional securities and the transaction costs of trust inherent to them as legal/compliance overhead.

Applied a market solution to problem of allocating scarce and valuable resource (Eric’s time as big brain nerd)

Maximized subjective value of Eric and his Orb buyer patrons, paying Eric for his time and allowing the person with the most valuable question to receive answers.

“Regulatory arbitrage”

By now we have addressed many of the common tropes trotted out by uninformed, knee-jerk skeptics and even career skeptics. However, the highest echelon of crypto criticism I think comes from folks like Molly White and others, who present seemingly measured, thoughtful and researched criticism that is hard to argue against. However, there is a pernicious change of tack that looks at the $0.10 cost of sending $10,000 of USDC to Pakistan or India from America and concludes that this is “regulatory arbitrage” of KYC/AML laws, and that the apparent derived value of crypto is wholly due to avoiding laws that prevent financial crime. Watch the below clip from a mainstream media style debate where Molly states said case:

Did you catch the sneaky supposition in this argument? We established there are economic transaction costs of trust in traditional finance where direct counterparties are always required.

Moving value in trad-fi requires complex webs of trust between intermediaries, and the laws and regulations that govern these webs of trust go beyond just Know Your Customer rules and Anti-Money Laundering provisions. Much more fundamental than those laws are laws governing transparency, reporting, conflicts of interests between fiduciaries and their clients and more. These are all huge overhead costs in most financial institutions! Trad-fi laws are a giant complex ruleset learned over time to manage an equally complicated web of counterparties and trust that are required to have functioning economy.

Molly is essentially saying;

“well if we force crypto protocols to fit into the old framework of laws meant to govern direct intermediaries, the use case of crypto will go away as it’ll be just as expensive as the trad-fi services that are kosher for you to use in the eyes of the establishment.”

No shit, but its important to realize how damaging this position is, because it assumes all these rules are just and required where direct intermediaries are not assumed, even KYC or AML, which stops less than 1% of illicit activity but costs everyone their financial anonymity.

As an American, it will never be reasonable to treat people seeking financial anonymity as criminals in a country where abortion is illegal in many states, sex work and medical marijuana are still criminalized, and state-by-state rollbacks on the rights of everyone from families seeking gender-affirming healthcare to interracial couples are being discussed as imminent threats.

Overall, it’s high time we start explaining our industry better than opportunist VCs and awkward libertarian nerds have managed to do so far. A lot depends on it, because as we can see, people in Western towers of ivory and power like Molly will paint it as just scams and tax dodging even if they may do so with the best intentions.

Hopefully this article has helped you learn how to argue against their pernicious narratives. This content is CC0, feel free to share it, copy it, or even claim it as your own and make some money off it. I don’t care as long as there’s a possibility that the Overton window can be shifted to preserve one of the most important innovations of our lives.